The Patrick Story

Stereotypical image of the mythical ‘St. Patrick’ - the man from God knows where.

The Story of Saint Patrick - patron saint of Ireland - has all the excitement of a great epic: the mystery man from God knows where who was kidnapped as a boy, enslaved, experienced a divine vision, escaped to freedom and returned to his persecutors as their saviour. Within his lifetime ‘Patrick’ converted a whole country to Christianity: not even Jesus or Paul had achieved that.

We all like a good story.

But is there more to the St Patrick Story than meets the eye? Must we believe all that we are told? Is it just a harmless myth and a bit of craic or is there a subtext in this story that is not good, that should be exposed for the harm it has done?

Doesn’t it strike you as curious that the St. Patrick Story is quite different from that of any other patron saint in these islands?

The major difference with ‘Patrick’ is that he made a journey to Ireland from somewhere else (significantly we aren't told where) with the express intention of converting the Irish to Christianity. Very few patron saints set out on a voyage to convert a whole country; none in these islands, except ‘Patrick’. Even the early Irish missionary monks who followed Patrick and traveled all over Europe, like Columbanus, were not so ambitious and evangelical like their supposed founder. They were surprisingly modest and did not set out to aggressively convert large ethnic groups. Isn’t it curious that they did not follow the aggressive example of their (alleged) founding saint?

In Britain St George of England was Greek and St Andrew of Scotland was a Galilean/ Palestinian, neither of whom had any connection whatever with these islands. They were just eminent holy men who were given the job. But that's another story in itself.

St David of Wales is noteworthy for being the only native born saint, but he led an unremarkable though worthy life, with none of the high drama attributed to ‘Patrick’.

It’s no wonder ‘Patrick’ is the only saint who has become a global brand. His story is loaded with subtext and all the necessary elements to hold an audience - tragedy, loss, persecution, divine intervention, salvation, redemption, forgiveness and finally triumph and success.

All this could be that the Irish were canny and picked the saint with a really good backstory. After all the Irish are the ones for a good story. They needed someone who was more than just a worthy old holy man.

But so what if it is just a good story without any basis in fact; where’s the harm in that?

My concern about the ‘Patrick’ Story is that it is in fact much more than a simple harmless myth that allows the Irish to celebrate their identity. I believe it is a very powerful myth loaded with subliminal meaning and images that has been created and used through the centuries to mould how the Irish see themselves and, by that, has allowed others to manipulate and control the Irish.

Who made the decision to make ‘Patrick’ the patron saint of Ireland?

That’s another of the many mysteries about the Man from God knows where. It’s clear it wasn’t the Irish people. It also begs the question: why have a patron saint? What purpose does it serve?

Although ‘Patrick’ was never canonised by Rome (most Irish saints weren’t, their sainthood is purely honorary), given how the ‘Patrick’ Story was used as a powerful tool of social control, it’s likely it was Rome some time after they seized control of the Irish Christian church in the 12th century.

*******

First doubts

My initial doubts about St Patrick surfaced when I realised that by 520AD, within just thirty years or so of ‘Patrick’s’ death (circa 490AD - the exact date of this is uncertain - like everything else with St Patrick), St Finnian in Clonard abbey in Meath had some 3000 monks under tuition. This was replicated in several other monasteries throughout Ireland in the early to mid-sixth century. Bear in mind that at this time Ireland had a population (it is estimated) of around 500,000 and internal travel was by no means easy. So to have such a large number of people spread over a wide geographical area, not just converted to Christianity, but to have taken holy orders, within such a short space of time suggested that ‘Patrick’ was not just a saint, but a wizard. In fact if this is true, St Patrick could teach Jesus and St Paul a thing or two about how to run a successful mission.

My doubts were further reinforced when I discovered that there were in fact already Christians in Ireland before ‘Patrick’s’ alleged mission.

Writing in 431AD , Prosper, a confidant of Pope Celestine said:

‘Pope Celestine ordained Palladius and sent him to the Irish believers as their first bishop.’ (my emphasis)

Bede repeats the same statement some two hundred years later.

There were also Irish Christian saints who predated Patrick. Such as:

St. Ciaran of Saighir

St Ailbhe of Emly

St Ibar of Wexford

St Declan of Ardmore

From this it seems reasonable to assume that ‘Patrick’ did not bring Christianity to Ireland. It was already there.

Palladius’ mission to Ireland in 431AD failed within a year. The Irish High King, Lóegaire mac Néill, chased him.

So the legend goes that ‘Patrick’ arrived the following year and his mission swept all before it. The same High King Lóegaire mac Néill, who had kicked out the Pope’s emissary the previous year, trembled before ‘Patrick’ apparently. However Prosper (and later Bede) do not mention Patrick following on from Palladius.

This also begs the question why did ‘Patrick’ not link up with the Christians already in Ireland? It would seem the obvious thing to do as a new missionary - work with what you’ve got and build from there. But there is no mention of these early Irish Christians in any of the writings connected to ‘Patrick’.

Could it be, I asked myself, that the apparent sudden growth of Christianity in the sixth century - that appeared immediately after ‘Patrick’s’ mission - was part of a much earlier trajectory and had nothing to do with ‘Patrick’? In other words Christianity had been well established in Ireland long before this ‘Patrick’.

Early records

St. Gildas

The other factor that convinced me to give ‘Patrick’ a wide berth was that no early Christian writers in Ireland or Britain mention this ‘Patrick’.

St Gildas (500–570) - thought to have taught St Finnian of Clonard - and the famous St. Columbanus of Bangor (543-615), himself a prolific writer and the Venerable Bede in England (672-735), an eminent early historian, all make no mention of this ‘Patrick’ and his allegedly highly successful mission to Ireland.

St Colum Cille’s biographer, St Adomnán of Iona (c. 624 –704) - whom Bede met - also makes no reference to Patrick in his story of Colum’s life. Colum Cille aka Columba (521 - 597AD) was born in Co. Donegal just thirty years after Patrick’s death. Surely ‘Patrick’ would have been a great influence on the young Colum? So why does Adomnan not mention ‘Patrick’ in his story of Colum’s life?

Evidence of Patrick

It was not until three hundred years after ‘Patrick’s’ death in the early ninth century that this ‘Patrick’ is first mentioned.

A monk, Muirchú, under the patronage of Bishop Aedh of Slébte (Sletty, Co. Laois) wrote ‘The Life of Saint Patrick’. His work was supplemented by Bishop Tirechan sponsored by Ultan of Ardbraccan (Co. Meath). Both their works were included in the Book of Armagh (807AD) along with writings claimed to be by St Patrick himself - his Confessions and his Letter to Coroticus.

It is upon these manuscripts that the whole ‘Patrick’ story is based.

So what do they tell us (or not tell us)?

First of all the manuscripts held today that are attributed to ‘Patrick’ himself - the Confessions and the Letter to Coroticus - are ninth, not fifth, century documents. So at best they are copies of the originals, but the originals don’t exist, leaving no evidence of any kind that they were written by ‘Patrick’. The manuscripts themselves are extremely vague about the author’s life story and in some places quite contradictory.

The Latin used by the author is poor. ‘Patrick’ acknowledges this and claims to be ‘a simple country person’, ‘ignorant’. Yet he also claims to be ‘noble’, the son of a Romano-British cavalry officer in one document and in the other to be the son of a ‘deacon’ and the grandson of a ‘priest’. Either, if true, suggests this was an educated family. ‘Patrick’ says he lived with his parents until he was taken into slavery in Ireland at the age of sixteen. By which time he, being Romano-British, should surely have been fluent in both spoken and written Latin.

After escaping slavery in Ireland when he was twenty-two ‘Patrick’ returned to his family home and did not return to Ireland for another ten years. By which time ‘Patrick’ is claiming the title of ‘bishop’. Clergy would have been taught in Latin. So by the time he got to Ireland in his thirties with the rank of bishop, this ‘Patrick’ should have been an accomplished Latin scholar. Yet the Latin text is written by someone not highly educated and not brought up as a Roman with Latin in daily use.

These manuscripts tell us nothing about how ‘Patrick’ spent his time after his escape from slavery in Ireland. He returns to Ireland after ten years claiming to be a bishop, but does not record how he came to be a bishop. Where did he study? Who ordained him? Who sent him to Ireland? What are his credentials? Presumably if the author made specific claims these could have been checked out. So best to leave it vague.

We know from Prosper writing in 431AD that there were already Christians living in Ireland before ‘Patrick’. As already mentioned, ‘Patrick’ makes no reference to these people. Similarly, Muirchú and Tirechan also make no mention of these early Christians when writing about ‘Patrick’s’ mission.

The writings of Muirchú and Tirechan develop the ‘Patrick’ legend to new heights of storytelling. They describe many events that ‘Patrick’ in his writings did not mention. They make much of how Patrick favoured Armagh. Muirchú writes that ‘Patrick’ intended to die in Armagh, and though an angel convinced him not to specifically go there (there’s no evidence that ‘Patrick’ ever did), the angel stated that ‘Patrick’s pre-eminence’ would be at Armagh. In the writings directly attributed to ‘Patrick’ he never mentioned Armagh. It was a later invention for political purposes.

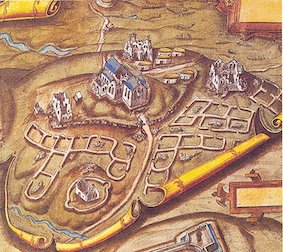

Armagh c. 5th century

This great emphasis on Armagh strongly suggests that the Patrick Story was part of the campaign to have centralised authority, the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland, sited in Armagh. Both sponsors of Muirchú and Tirechan, Bishop Aedh of Slébte and Ultan of Ardbraccan were active in this campaign.

Why is Armagh important?

The early independent Irish Christian Church was non-hierarchical. There was no central authority, no archbishop or cardinal. The church was founded on monasteries run by abbots or abbesses. Each monastery was independent and answered only to the local tuath or clan.

The structure of the early Irish Christianity was not unique to Ireland. Its structure was identical to that of the early Christian church around the Mediterranean until the Romans got hold of it after the conversion of Emperor Constantine in the fourth century and created a centralised hierarchy.

The move to create an ecclesiastical centre was part of a long term strategy to make the Irish church conform to the highly centralised and hierarchical Roman model.

‘Patrick’ was violent: the Irish submissive

Muirchú has ‘Patrick’ setting curses on people who did not accept his authority. Suddenly the ‘simple country person, and the least of all believers’ - as ‘Patrick’ described himself in ‘Confessions’ - was replaced by a ruthless religious zealot, even slaying druids and princesses and burning their books - 180 in all - in order to impose his religious beliefs on the supposedly gullible and passive Irish. The tone of the language and the action describes what amounts to a military assault on native Irish religious beliefs. This was not a missionary who came in peace. Whoever this ‘Patrick’ was, he certainly did not model his behaviour on Jesus or St Paul.

Also unlike Jesus and so many of the early Christians, ‘Patrick’ was not martyred or even persecuted. According to legend the barbaric Irish never laid so much as a hand on Bishop ‘Patrick’ in spite of his highly aggressive behaviour towards them, their beliefs and culture. The previously barbaric and warlike Irish suddenly surrendered to this single man.

Irish submission to foreign authority had begun.

‘Patrick’ apparently died peacefully in old age.

The shamrock and the snakes

The legend of driving the snakes out of Ireland and the use of the shamrock was never mentioned by ‘Patrick’, Muirchú or Tirechan. The snake legend was added in the thirteenth century and the shamrock as late as the eighteenth century.

There were of course no snakes in Ireland. This was a reference to the symbol of the serpent used by the druids who were eventually driven out of Ireland, but not in ‘Patrick’s’ time.

Druid symbol

Why has the ‘Patrick’ Story remained so popular?

So given that the ‘Patrick’ legend is so suspect, how and why has it survived the centuries so well and why should it matter in the 21st century?

In the early Christian period hagiography was the norm. The scribes were early propagandists or ‘spin doctors’. Writers talked up their champion and ascribed all kinds of super-human qualities to them to further their cause - in ‘Patrick’s’ case the creation of Armagh as the ecclesiastical centre for Ireland. So legends like ‘Patrick’ were not unusual and were believed without question as an act of faith for many centuries. The people loved a good story well told.

Even today I have been amazed at the how easily the media and the world of academia buys into the story of St Patrick without question. Academics who are normally so sceptical of all other Irish legends and demand provenance for historic manuscripts, accept that the documents ‘Confessions’ and the ‘Letter to Coroticus’ were indeed written by ‘Patrick’ without any evidence being available. None dare even raise the slightest doubts! This makes me suspicious. These outlets - the media and academia - (used to) pride themselves on their objectivity and in challenging accepted opinion. Why don’t they challenge the ‘Patrick’ Story?

The emperor (the saint) has no clothes

The Ulster Museum in Belfast, like other museums throughout Ireland, make bold public assertions about the provenance of the ‘Patrick’ manuscripts, copies of which are on prominent display, but they can produce no evidence to support their claims(1) and remarkably no one knows where the originals are held. The phrase that is widely used is that it is ‘generally accepted’ that these documents were written by ‘Patrick’; ignoring the fact that there is NO evidence that the author, ‘Patrick’, is a real historical figure who wrote the documents attributed to him.

So it is academic consensus that holds the ‘Patrick’ Story together and few, if any, are prepared to break the spell and risk the contempt of their peers and the public for daring to attack this powerful icon of Irishness.

The churches - both Catholic and Protestant - are also keen to keep the legend alive. It’s one of the few areas of Irishness they agree on.

Likewise Irish nationalism holds ‘Patrick’ close to its heart, even though he was allegedly a ‘Brit’ and there were many other more deserving native born saints to chose from - Finnian, Columcille, Columbanus, Íte and Comgal to mention just a few.

So anyone casting doubt on the ‘Patrick’ Story will risk the ire of academia, of Irish nationalism and of the churches.

It’s Politics, not religion

Beyond a strong desire to conform among academia, I have concluded that the reason ‘Patrick’s’ legend has survived into the 21st century and has become a global brand, is not religious. It's politics of a very sinister nature.

The Roman Catholic Church, which finally conquered the independent Irish church in the 12th century on the back of the Norman invasion in 1170AD, eagerly adopted the Patrick legend for two reasons (even though ‘Patrick’ was never canonised by Rome).

The first was that the creation of the ecclesiastical centre in Armagh was part of a long campaign to introduce Roman systems of church governance into Ireland, such as the central power exercised by bishops as opposed to local abbots, the use of the Roman system of dating Easter and most importantly - collecting rent. The ‘Patrick’ Story with its focus on Armagh was central to this campaign.

Irish gold lunulae circa 2000BC

Secondly, and more importantly in the modern age, was the reinforcement of the ancient narrative that all good things in Ireland have come to it from abroad, especially in the matter of religion. It was crucial to the English and to the Roman See in their subjugation of Ireland, that the country came to see itself as a backward, primitive society in need of an imperial power to avoid them killing each other and lapsing back into their heathen ways. St Patrick was the iconic symbol of this theory.

‘Patrick’ brought guilt and shame to Ireland.

The Irish had enslaved this saintly foreign man as a boy, mistreated him and pursued their heathen ways. But he, being a superior being (not Irish), forgave them, returned to them ordained by God himself to destroy their heathen ways, to offer redemption for their sins, to bring them to the light. Ironically it was Patrick who then began the enslavement of the Irish!

This narrative is still in evidence today. The ‘Patrick’ Story fitted the needs of the empire builders; in fact the ‘Patrick’ Story was and still is the cornerstone of this narrative.

The Ardagh Chalice. 8th C. National Museum, Ireland

I am always struck when researching Irish history how prevalent this narrative is among academic and non-academic historians today. These are not just Church historians, but English and American academics and sadly the Irish themselves. Whether it is in religion, metalwork, pottery, writing, boat-building, anthropology or architecture we are always told it all came from outside Ireland. Nothing was accepted as originally Irish. The Irish were great copiers, they created nothing original and influenced very little elsewhere is the subtext.

The iconic Newgrange 'passage tomb' is a good example.

Newgrange, Co. Meath (restored 1960s)

It was not until the 18th century that it was finally accepted that the Vikings did not in fact build Newgrange. It was the Irish! Then it took another two hundred years to convince the academics that this structure and many others were built before Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids - by the Irish! It was not until the mid-twentieth century that it was accepted that these structures were sophisticated astronomical observatories and not simple burial chambers.

So strong is this narrative about Irish backwardness that it seemed impossible to classically trained historians that there could have been a civilisation in Ireland with such advanced technical skill.

In the same vein, the reason why the Romans never conquered Ireland is fitted into this narrative: the Romans were disinterested, we are told. There was nothing in Ireland to make it worth their while. Ireland was all bog and bog-trotters. This is taught in Irish schools of all denominations - north and south - to this day. It is manifestly untrue. Ireland had huge natural resources of copper, wood, skills in metalwork and farming, livestock and people that were much needed by Rome. Instead of conquering, as was their habit elsewhere, Rome traded peacefully with the Irish.

The Viking myth

Four hundred years after the Romans, the Vikings showed great interest in Ireland, describing it as a ‘land of butter’, but significantly they were unable to conquer the island. They had to satisfy themselves with a few toeholds in Dublin, Waterford, Limerick and Galway where they paid tribute to the local king who valued their trade. They were frequently chased back to England where they had little trouble subduing large areas of that country.

Yet if you listen to many historians the impression given is that the Vikings more or less conquered Ireland until Brian Boru finally defeated them.

The truth is the Vikings were defeated on several occasions on both land and sea especially in Ulster, where the Uladh prevented any significant Viking settlement. The Book of Invasions tells that the Vikings raided Ireland twenty-five times over a thirty year period from the first raid in 795AD. That’s one raid a year. Hardly an invasion.

But if you listen to many historians of the period you would be sure the island was in uproar as a result of Viking raids.

Viking dreki or longship

However it was the English who finally helped disprove this theory of disinterest, when the Anglo-Normans came by invitation of Pope Adrian IV and the King of Leinster to Ireland in 1170. They were so impressed that they have never left; showing an intense interest in the place ever since.

The beginning of Irish History

Effectively Irish history began with ‘Patrick’ in the fifth century. Everything before ‘Patrick’ is regarded as misty-eyed legend, the stuff of fairy-tales and has been closed off to the Irish through the destruction of records. ‘Patrick’s’ mission is seen as ‘year zero’.

Because few resources are invested in the pre-patrician era, few discoveries are made to shed much light on this period.

We are told as part of the ‘Patrick’ Story that there were no books in Ireland before ‘Patrick’ arrived. The unquestioned narrative is that Christianity, namely ‘Patrick’, brought writing to the island. But Muirchú clearly tells us that ‘Patrick’ burnt many Irish books. Whether this actually happened or not is not the point here. The point is that an Irish monk writing in the eighth century - Muirchú - believed that many books existed in Ireland prior to ‘Patrick’. How many ancient books were destroyed? What did they tell of ancient Irish culture?

"Ireland would have been the richer had not the fears or bigotry of the priests discouraged the reading of pagan poems and romances, and thrown thousands of MSS [manuscripts] into the flames." (my emphasis)

(Legendary Fictions of the Irish Celts, by Patrick Kennedy; New York and London, Macmillan; [1891])

In all this we are asked to believe that prior to St Patrick arriving in Ireland there was no organised religion in Ireland and no books. Yet, according to the conventional narrative, within a short space of time - less than a century - the Irish were world leaders in both Christianity and books. A sudden turn around for a primitive, ignorant people, is it not?

1 Ulster Museum FOI Response 12 January 2016